|

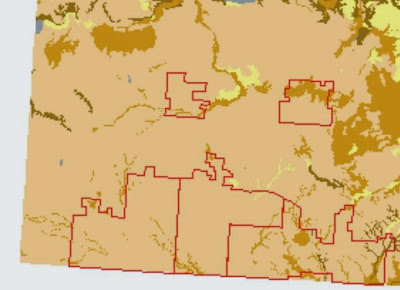

| Mixed grass prairie on the Auvergne Wise Creek PFRA Community Pasture |

The PFRA pastures are part of our prairie heritage, representing an investment Canadian taxpayers have been making for more than 75 years. We made that investment because we recognized that it would reap public benefits: not only holding the soil during drought, but diversification for farmers, food security values for the prairie provinces, support for the small to medium beef producer, biodiversity, soil conservation and carbon sequestration, water conservation, protection of heritage lands and the archaeology and history they contain.

Taxpayers have paid into the conservation objectives of the PFRA for decades precisely to serve and protect those wider interests. Over the years this investment has built up an ecological and economic value that should not be placed in the hands of private citizens without proper governance and management oversight in place. Conservation easements and stocking rates set in distant cities will not be enough to keep the ecology of these grasslands intact. What would Saskatchewan's north look like if we sold our Crown forest lands or if we gave the leaseholding forestry companies some minimal guidelines and then let them have at it?

We don't do that because we believe that our forests must be regulated and owned by the Crown so that the wider pub interests in having healthy forests are served. Sure we sell forestry leases to forestry companies, but the Province strictly regulates how the land is treated under the lease and ecological matters and concerns about rare species and invasive species are included in the planning and monitoring for any forestry operations.

In fact, we have an entire Forest Services Branch in Saskatchewan's Ministry of Environment that ensures that our Crown forest lands are being managed well on our behalf. Here is a quote from the Province’s Forest Services Branch website:

“Saskatchewan, usually thought of as a prairie province, is actually more than half forests. Most of these - more than 90 per cent - are provincial Crown forests, owned by the people of Saskatchewan. On their behalf, the Ministry of Environment ensures that these forests are sustainably managed.”

Take a look at the legislation we have to protect our forests, and scan through a Forest Management Agreement Area Standards and Guidelines document. Almost 70 pages spelling out exactly how the forests are to be managed on public lands and how the management guidelines will be enforced. And the Forest Services Branch has the people to do it: forest protection staff, fire management staff, forest ecologists, Forest Management Planning experts, silvaculturalists, Forestry enforcement staff, compliance officers, ecosystem modelers, inventory specialists, research analysts, Forest management evaluators, Ecosystem classification and monitoring experts, and so on.

All to serve an industry of approximately 300 forestry firms employing roughly 9,000 people, generating $750 M in revenue.(from www.gov.sk.ca/keysectors).

Meanwhile, there are 7,300 beef operations in Saskatchewan (according to the Western Beef Development Centre), employing more people and generating much more revenue. In fact our cow-calf industry alone produced cash income in 2011 of $1.4 billion (from a 2012 Stats Canada quoted in a Canadian Cattleman Association report by Kulthresthna et al)

What does Saskatchewan have for staff monitoring the use of its six million acres of publicly owned native grasslands? Do we have ecologists, research analysts, grassland management experts, compliance officers, ecosystem classification staff, monitoring experts? No. Sask. Agriculture does have a few agrologists, but nowhere near enough range specialists to handle all the native grass they are responsible for. How much real monitoring will be done if the 1.8 million acres in the PFRA system are leased out to private grazing associations made up of people who are not used to managing vast tracts of grassland?

Part of this difference in our oversight of forest versus grassland is cultural. The general public recognizes the value of forest as natural landscapes that must be taken care of. People get concerned when they drive by a well-managed clear cut of forest (our boreal forests recover better when they are cut in large blocks), but few express concerns over the loss and degradation of our native prairie.

Granted, the cattle industry is not the forestry industry; there are some important differences. No one would realistically expect a full "Grasslands Services Branch" to be established matching our Forestry Branch, but why not develop a non-governmental grassland management agency funded by resource revenues and grazing fees to oversee the stewardship of the Province's Crown grasslands while ensuring that both the private interests of our cattlemen and the wider public interests of taxpayers are well served?

Sooner or later Canadians will see that our grasslands are as ecologically and spiritually vital to our nation as our forests. Better to see the light now than to foolishly privatize our Crown grasslands only to discover in decades to come that we have made a terrible mistake. If we let the Province sell off our Crown grasslands and then wake up one day thinking, gee, we should do more to protect native prairie, we would have to either embark on buying back these lands or find policy tools to manage for grassland conservation on private lands. Either way, we end up struggling against private property rights. Right now, we still have these Crown grasslands where they need to be, where we can ensure that they are managed well for the birds, the pronghorn, the swift fox, and all the other wild prairie creatures that deserve to have their habitat protected just as much as their counterparts in our forests.

|

| Sharp-tailed Grouse |

.jpg)