|

| image from the cover of the Ecojustice report on Canada's species at risk laws |

Last week's Emergency Order from Environment Canada was a clear signal that more needs to be done in this province to protect its endangered species. It is no coincidence that the first Emergency Order ever issued under Canada's Federal Species at Risk Act was for a species that Saskatchewan has allowed slip away.

Saskatchewan is one of four provinces and territories that have yet to pass their own species at risk legislation. Ecojustice, an NGO that uses the law to defend Canadians' right to a healthy environment, published a report exactly one year ago that grades the provinces on their record of protecting endangered species. The report, titled Failure to Protect: Grading Canada's Species at Risk Laws, gives Saskatchewan an "F".

Why did we get the lowest possible grade? Simple. We don't have any specific standalone legislation that protects species at risk properly. We have a Wildlife Act, which is really about managing game species for hunters, but, it was later amended to to establish a process for evaluating the status of species at risk (it should be noted that this hard-won amendment was fought for by the indefatigable Lorne Scott, the best Environment minister this province has seen. Lorne did his best at the time, but would be first to admit that more is needed today). Ecojustice, in its report, states strongly that this is not enough. It calls the listing process in our Wildlife Act "vague [and] discretion-laden" and says it "allows, but does not require, the Minister of Environment to consider the recommendations of a committee created under the Act to identify species at risk."

The problem with that kind of discretion is that ministers of Environment in this Province, no matter what the political stripe, are always trumped by ministers of economic development, resource development, and agriculture. The Environment Ministry is often told to shut up and toe the line when there are policy conflicts between resource development or farming on the one hand and the environment on the other.

The Act does say you can't kill a species at risk, and prohibits the disturbance of den and nest sites. That is a minimum, but not near enough to help creatures in steep decline from development pressure destroying their habitat. Real Species at Risk legislation always sets out a clear schedule compelling the government to identify and protect the habitat the species need to survive and recover. Saskatchewan's Wildlife Act does neither. As well, Species at Risk legislation must establish meaningful mechanisms to activate a recovery plan for the species at risk. As the Ecojustice report points out, our Wildlife Act "describes a process for preparing recovery strategies but has no mandatory provisions requiring them to be science-based. The Act also doesn’t establish a timeline for when recovery strategies should be produced, what they should contain, what course of action they can prescribe, what must be considered during their preparation, or what the Minister must do with them."

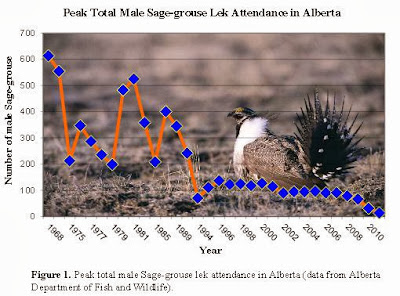

But here is the bottom line. If the existing laws are effective in protecting Saskatchewan's species at risk, then why are there only recovery plans for two species at risk, when the Wildlife Act itself identifies 15 species at risk? This is a ridiculously low number, considering that five of them are already extirpated, and the Federal list of Species at Risk shows 64 species at risk in Saskatchewan. For the two species that have had a recovery plan written (Greater Sage-Grouse and Woodland Caribou), it has been far too little far too late.

To hear more on this topic and why Saskatchewan needs species at risk legislation with some meaningful language, tune into CBC Radio's Blue Sky on Monday, when Professor Andrea Olive, a recognized authority on Canadian species at risk legislation from the University of Toronto (but born and raised in Saskatchewan), speaks during the phone-in show. If you have a chance, call in to voice your concerns. If you miss the show you should be able to catch it later with a link on their web page.

|

| Professor Andrea Olive, image from U of T web page |