.jpg) |

| the Battle Creek PFRA lands that helped to launch a new defense of wild lands in North America (image courtesy of Branimir Gjetvaj) |

In my most recent post here (In Defense of Wildness and Federal Lands: the Stegner Legacy Part 1), I wrote about how a single letter written by Wallace Stegner in 1960 led to the passing of a piece of American legislation (The Wilderness Act) that remains one of the continent's best pieces of policy protecting public wild lands. If Canada had similar legislative protection for its Federal grazing lands stewarded for 75 years by the PFRA system, we would not be scrambling to ensure that they remain well-managed public grasslands once they are transferred to the provinces.

This difference between Canada and the United States, which retains its Federal grazing lands, is made even more trenchant when you realize that Stegner traces his concept of the spiritual need for wilderness to a piece of land that is now contained in one of Canada's most ecologically rich PFRA pastures, Battle Creek. This astonishing fact came to me three weeks ago via an email from Bob Peart, a great proponents of grassland conservation and the new executive director of British Columbia's Sierra Club. The email contained a message sent to Bob by Jim Foley, an amateur Stegner historian from Alberta who has done some digging into the author's roots on the Canadian Plains.

As I read the email and Stegner's Wilderness Letter, I thought about the young Wallace Stegner and his brother running half wild themselves with the black-footed ferrets, sage grouse and swift foxes of their homestead in the southwest corner of Saskatchewan on the US border. When you read the Wilderness Letter, it becomes clear that, more than any other landscape, the wild Canadian prairie--the largest pieces of which for now remain protected on PFRA pastures such as Battle Creek, Govenlock, Val Marie, and many others--inspired Stegner and taught him why wild places must be preserved.

"I learned something from looking a long way, from looking up, from being much alone. A prairie like that, one big enough to carry the eye clear to the sinking, rounding horizon, can be as lonely and grand and simple in its forms as the sea. It is as good a place as any for the wilderness experience to happen; the vanishing prairie is as worth preserving for the wilderness idea as the alpine forest."

Speaking to Jim Foley on the phone, I learned that he would like some help forming an interdisciplinary committee (of local people in the southwest, as well as conservationists, government,

literary/culture people, historians, etc.) to advance the idea of protecting the

Stegner land and as much of Battle Creek pasture as possible in honour of

Stegner and his "idea of wilderness" as expressed in his letter.

|

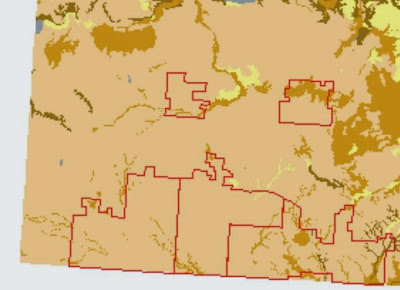

| this map shows in red boundaries the three PFRA pastures south of the Cypress Hills along the US border in Saskatchewan's southwest: from left to right--Govenlock, Nashlyn, and Battle Creek |

I think it is a brilliant idea. The

Wilderness Act and the work of Stegner and the Sierra Club has over

the last 50 years had a tremendous influence on North American wilderness thinking and advocacy.

Jim suggests connecting a strip of Battle

Creek pasture including the Stegner homestead land to Govenlock Community Pasture through the neighbouring Nashlyn PFRA pasture. The land would then become The Wallace Stegner National Wildlife Area,

a significant corridor of grassland conservation named for the man whose defense of North American wilderness took its origins from the

Canadian prairie in 1914. In honour of Stegner's roots and his recognition that cattle grazing is not incompatible with prairie wilderness, the land would continue to be grazed sustainably by local cattle producers as it has been under the PFRA for nearly 80 years.

Passages like the following from the Wilderness Letter could be placed on a brass plaque and mounted at a roadside historic monument on the boundary of the Battle Creek Pasture:

"The reassurance that there are still stretches of prairies where the world can be instantaneously perceived as disk and bowl, and where the little but intensely important human being is exposed to the five directions of the thirty-six winds, is a positive consolation. The idea alone can sustain me."Stegner concluded his historical Wilderness Letter with a phrase that has become part of the literary heritage of wilderness defenders:

"That is the reason we need to put into effect, for its [wild lands'] preservation, some other principle than the principles of exploitation or "usefulness" or even recreation. We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in. For it can be a means of reassuring ourselves of our sanity as creatures, a part of the geography of hope."

In this part of the world, where the Canadian government has abandoned its commitment to conserve our Federal grasslands, Jim Foley's vision for one piece of the southwest corner of Saskatchewan has sent a ray of hope into a geography where it is far too easy to throw up one's hands in defeat. And, just for the record, the people who care about grassland and a strong and diverse grazing economy in this province are nowhere near giving up. We are just getting started.

If you would like to help Jim and others see his vision through, if you want one day to be able to drive to the edge of the Wallace Stegner NWA and look in, fire me an email at trevorherriot@gmail.com and I will put you in touch.

|

| another gorgeous shot of Battle Creek PFRA by Branimir Gjetvaj |