|

| Ponteix rancher, Orin Balas (left) showing his excellently managed prairie to Bob McLean from the Canadian Wildlife Service |

The Province is saying it will dismantle Saskatchewan's provincial

community pastures system. Not good news, but here is a four-step process on how

to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear:

1. First, for inspiration and food for thought, take a look at

this short, ten minute video (below) put out by the South of the Divide ConservationAction Program (Sodcap).

It is called "Prairie Pride" and features some of Southwest Saskatchewan’s best private managers

of native rangeland, ranchers who graze large expanses of Crown grasslands on

long-term private lease holdings—much of which would be included under the

Wildlife Habitat Protection Act.

Listen to what they have to say. The video contains a hopeful, aspirational message that speaks to possibilities that could help us make that silk purse.

Listen to what they have to say. The video contains a hopeful, aspirational message that speaks to possibilities that could help us make that silk purse.

2. Now, keeping in mind the stewardship ethos expressed so well in the video by those three ranchers—good people I have had the privilege to meet—let yourself imagine a partnership between private interest (cattle producers), the wider public interest (government administered Crown grasslands of various kinds), and the local community interest of rural areas—a partnership that would aim to foster a mix of private and public benefits: economic, cultural, social, and ecological, including improved carbon sequestration and climate resiliency.

How? Take the gospel of stewardship and prairie protection we heard from the ranchers in the video and use public policy to help it spread across our prairie ecozone to all land managers—First Nations, farmers, mixed farmers and other ranchers.

3. Next, consider the moment and its rich possibilities:

a.) The last of the former PFRA federal community pastures, and the biggest ones with the highest ecological values in terms of biodiversity and species at risk density, are poised to be transferred to Saskatchewan and then placed into private management for cattle production by groups formed by the former grazing patrons.

b.) First Nations in the province are concerned about the

sell-off of Crown lands and meanwhile are increasingly interested in land

management opportunities.

c.) Organizations launched by ranchers, from Sodcap to Ranchers Stewardship Alliance to the Prairie Conservation Action Plan (PCAP) are concerned about the business risks that Species at Risk pose for private producers. This is a reality. If land managers see SAR as a liability, bad stuff happens.

d.) The Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture just announced that it is planning to close its provincial community pastures program, but it is inviting the public to join in a discussion on what should happen to these fifty pieces of land containing 780,000 acres, some of which is native and some of which is tame grass.

c.) Organizations launched by ranchers, from Sodcap to Ranchers Stewardship Alliance to the Prairie Conservation Action Plan (PCAP) are concerned about the business risks that Species at Risk pose for private producers. This is a reality. If land managers see SAR as a liability, bad stuff happens.

d.) The Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture just announced that it is planning to close its provincial community pastures program, but it is inviting the public to join in a discussion on what should happen to these fifty pieces of land containing 780,000 acres, some of which is native and some of which is tame grass.

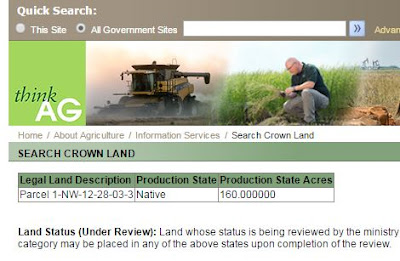

4. Finally, take a look at maps that show the federal and provincial pastures, as well as the Wildlife Habitat Protection Act grasslands nearby—here is an example below.

Now, keeping the grazing needs of cattle producers in mind, consider that as of

today all of that land is still Crown provincial land—most of it leased out or

soon to be leased out privately—but as Crown land it remains an instrument of

public policy. Interesting possibilities come to mind, but any seizing of this

opportunity would have to arise from the cattle producers of the region, but

then widen to include the interests of the public that would ultimately be

helping to absorb the costs of any programming or support.

Each region has its own soil and climate and therefore may need its own solution—a solution initiated locally that would honour and take advantage of the two kinds of range management knowledge that have been keeping the best of our Crown grasslands in good condition for generations: one, the traditional, intergenerational knowledge of private managers, which reaches back through some Indigenous land managers into the distant past, and two, the science of the range ecologists and biologists who support and work closely with private cattle producers.

With a new vision of how public lands, private interest and the community can work together in grassland regions, and the right support from the conservation community and federal and provincial governments, those two sides of range management knowledge and science could ensure that the example of stewards like those shown in Prairie Pride will not only live on in one corner of the province but will begin to spread to other areas as well.

Who knows? One day the pipits, longspurs, shrikes and burrowing owls that have vanished from large portions of their range might return. Once a better private-public bargain is in place and producers are feeling supported and appreciated, the ethic of stewardship could even extend to grassland restoration, helping to connect some of our isolated expanses of native grassland with richer habitat suitable for cattle production as well.

In the bargain, Saskatchewan could be proud of its contribution to national protected areas and carbon sequestration targets by working with land managers to increase our percentage of the prairie ecozone under protection and our net storage of carbon in soils under well-managed perennial cover.

Each region has its own soil and climate and therefore may need its own solution—a solution initiated locally that would honour and take advantage of the two kinds of range management knowledge that have been keeping the best of our Crown grasslands in good condition for generations: one, the traditional, intergenerational knowledge of private managers, which reaches back through some Indigenous land managers into the distant past, and two, the science of the range ecologists and biologists who support and work closely with private cattle producers.

With a new vision of how public lands, private interest and the community can work together in grassland regions, and the right support from the conservation community and federal and provincial governments, those two sides of range management knowledge and science could ensure that the example of stewards like those shown in Prairie Pride will not only live on in one corner of the province but will begin to spread to other areas as well.

Who knows? One day the pipits, longspurs, shrikes and burrowing owls that have vanished from large portions of their range might return. Once a better private-public bargain is in place and producers are feeling supported and appreciated, the ethic of stewardship could even extend to grassland restoration, helping to connect some of our isolated expanses of native grassland with richer habitat suitable for cattle production as well.

In the bargain, Saskatchewan could be proud of its contribution to national protected areas and carbon sequestration targets by working with land managers to increase our percentage of the prairie ecozone under protection and our net storage of carbon in soils under well-managed perennial cover.

Now that would be prairie pride times ten.

|

| Govenlock area rancher Randy Stokke on a Sodcap field tour |