Depending

on who you listen to, livestock are either destroying the planet or saving it.

For those who argue that livestock are a dead loss to the planet, the primary source of data has always been the 2006 United Nations Food and Agriculture

Association report called "Livestock's Long Shadow," which, among other things,

blames cattle production for a high proportion of the planet's greenhouse

emissions.

That single document has cast its own long shadow on every subsequent discussion of whether the world would be better off without ruminant livestock.

That single document has cast its own long shadow on every subsequent discussion of whether the world would be better off without ruminant livestock.

|

| from the Cowspiracy website |

Then along came Cowspiracy, a popular documentary that stepped up the anti-livestock argument with Indiegogo crowd-funding, a Michael Moore-style narrative, and an all or nothing conclusion that promotes veganism as not merely an environmentally-sustainable lifestyle, but a panacea for our ailing planet.

Cowspiracy, now on Netflix, claims to have used the best science

available--or at least the best science supporting their black and white

thinking. We can assume that one piece of research they gave a miss was this study published in Nature conducted by a

group of scientists working at 40 sites on six continents, including the

University of Guelph's Andrew MacDougall.

They also did not check with Tim Flannery, scientist, author of The Weather Makers, and chief commissioner of the Australian Climate Change Commission, who is on record saying that livestock grazing today is a sustainable use of grassland: "If we get the stocking levels right, we get the management techniques right and the management of water and of biodiversity right, I think we can have a very sustainable system of livestock management."

|

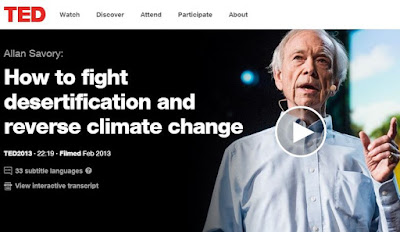

| Allan Savory on TED |

Meanwhile, early in 2013, holistic grazing guru Allan Savory gave a controversial Ted talk with more than three million views online in which he describes his own panacea for the climate's woes--more grazing. But not just any kind of grazing. Savory is famous for promoting his “holistic range management” brand of grassland management, in which densely packed groups of livestock graze an area for a short duration and then are moved to let it recover—a practice that many livestock producers are adapting under the name “mob grazing.”

In August 2014, however, British pundit and environmentalist George Monbiot, interviewed Savory and dismissed his theories in an article in The Guardian.

Shortly after that, Colorado sustainability promoter Hunter Lovins shot back with her own Guardian op-ed in defence of Savory and “holistic range management”.

OK—let’s stop right there. Following this debate over the past decade has given me a bad case of tennis-spectator neck.

All of the experts make compelling arguments. Even the Cowspiracy film makers have their charm and some of what they say about feedlot agriculture is undeniably true. But they did not look at the wider ecological issues for natural grasslands that scientists and writers like Flannery have explained vis a vis the role livestock plays in replacing absent native grazing animals.

And, as much as I agree with Allan Savory that grazing livestock is an important way for us to restore carbon to our grassland soils, I am not entirely convinced that his system of intensive grazing works everywhere. I may not like the way Monbiot cherry-picks in his critique and dismisses Savory as a quack, but I agree with him on several points about the problems with Savory’s grazing theories. But then I read Hunter Lovins’ defence of Savory and am confused all over again.

That was when I decided to abandon the experts from far away and look for a local one. In part II of “Cattle and the Fate of the Earth”, I ask Saskatchewan rancher, conservationist, and biologist Sue Mihalsky for her thoughts on Savory and his holistic range management system.

In August 2014, however, British pundit and environmentalist George Monbiot, interviewed Savory and dismissed his theories in an article in The Guardian.

Shortly after that, Colorado sustainability promoter Hunter Lovins shot back with her own Guardian op-ed in defence of Savory and “holistic range management”.

OK—let’s stop right there. Following this debate over the past decade has given me a bad case of tennis-spectator neck.

All of the experts make compelling arguments. Even the Cowspiracy film makers have their charm and some of what they say about feedlot agriculture is undeniably true. But they did not look at the wider ecological issues for natural grasslands that scientists and writers like Flannery have explained vis a vis the role livestock plays in replacing absent native grazing animals.

And, as much as I agree with Allan Savory that grazing livestock is an important way for us to restore carbon to our grassland soils, I am not entirely convinced that his system of intensive grazing works everywhere. I may not like the way Monbiot cherry-picks in his critique and dismisses Savory as a quack, but I agree with him on several points about the problems with Savory’s grazing theories. But then I read Hunter Lovins’ defence of Savory and am confused all over again.

That was when I decided to abandon the experts from far away and look for a local one. In part II of “Cattle and the Fate of the Earth”, I ask Saskatchewan rancher, conservationist, and biologist Sue Mihalsky for her thoughts on Savory and his holistic range management system.

I think that the issue giving livestock a bad name is not necessarily grazing grasslands, but the destruction of forests to create more grazing land. Any grassland grazing model that closely mimics how wild herds of ungulates would have grazed makes perfect sense to me, and I have no objection to that. But destroying forests, over-grazing, and allowing cattle to degrade riparian areas are not OK. And if we have to do those three things in order to produce enough beef for the planet at current consumption rates, then I think we do need to reduce the amount of beef we eat.

ReplyDeleteVery astute, Marie. Ideally I would like to see grassland ranchers receive higher prices for their beef. That would help them cover the costs of conservation of habitat and lower stocking rates and still let them make a viable living on native grassland (which now sells for $80,000 a quarter). That way a reduction in the amount of beef consumed would not penalize the ranchers who are good stewards.

DeleteBTW, I read your book "Grass, Sky, Song" last year while spending several weeks in the Great Plains. I'd never been in the prairie but had always felt a strong pull. We were mainly in the Flint Hills, and I found the prairie to be just as compelling as I'd hoped it would be. It's a landscape that requires one to slow down and look closely to see what makes it beautiful--panoramic sunsets aside. I loved the book and thought you made some very good points about management of our remaining natural areas, as well as the restoration of degraded land. I've been a volunteer with our DNR for eight years doing restoration work and it sometimes feels like you're bailing a sinking ship with a teaspoon. We do tend to hold a romanticized idea of "the good old days" and a desire to return the land to some past glory, but what past? At any rate, the book really spoke to me--thanks for writing it. And thanks for liking our Facebook page! I also write a blog, "The Rambling Wren," at marierust.blogspot.com.

DeleteThat is wonderful, Marie. I did look at your blog and thought, yep, this is a kindred spirit. Your bird paintings are vivid and inspired. I am sure they are even better in person. I always say if I tire of writing and grassland advocacy I am going to dig out my paint brushes and watercolours. Let me know if you ever come to visit the northern plains here where the grass is shorter but a few of the grasslands are still pretty big. Thanks for reading GSS and for getting in touch.

DeleteI definitely will!

ReplyDeleteSuch a great post! Gave me a lot to think about. Thanks!

ReplyDeletemore soon on this topic . . .

DeleteThe personal statement for medical school gives the admissions committee the inside scoop of who you are and if you have the heart to be a doctor. See more biology homework answers free

ReplyDelete